The trial of the Eugowra escort robbers furnished the citizens of Sydney with one of the biggest sensations that had ever been provided for them in the criminal sphere, and very little else was talked about in the city during the several days over which it extended.

|

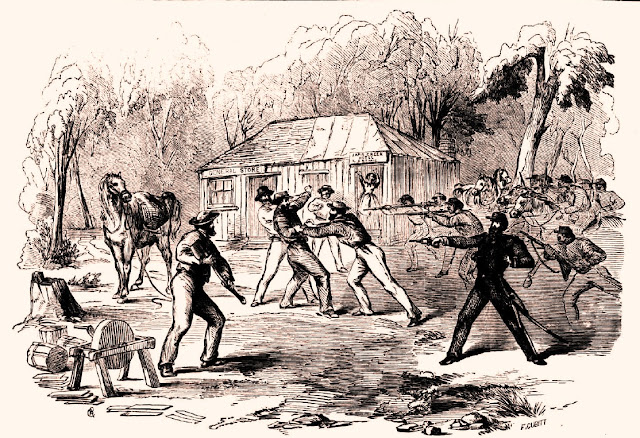

| Gardiner's House and Scene of His Capture at Apis Creek |

Manns, Fordyce, Bow, and McGuire were placed in the dock, Mr. (afterwards Sir) James Martin and Mr. Isaacs appearing for the defence.

After some delays, the procession of witnesses began. Sir F. Pottinger and Inspector Sanderson gave evidence relating to their adventures in search of the gang, while Condell, Moran, and Fagan described the sticking-up at Eugowra.

Evidence was called to prove the ownership of the gold, also that the rifles and cloak found at the deserted camp belonged to the Queen; and then came the evidence for which all were anxiously waiting—that of the approver Daniel Charters.

Having entered the witness-box and been sworn to speak "the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth", Charters proceeded to tell his story, as follows:– I lived at Humbug Creek, on the other side of the Lachlan. On the 12th June last, when I was driving some horses near Mrs. Pheely's station, called the "Pinnacle", I met Frank Gardiner, John Gilbert, and the two prisoners. Bow and Fordyce. Gardiner is a bushranger in that part of the country. Gardiner rode up to me about fifteen yards in advance of the others, and said he wanted me to go with him for a few days; I said I could not, for if seen with him I should be thought as bad as him. He said I must go, as he wanted me to show him the road to some place that he did not name. Gardiner had a double-barrelled gun slung to his horse, and two revolvers on his person; Gilbert and Fordyce were armed also. When I declined going with him, Gardiner put his hand on his revolver, and said, "I've come for you, and you must go." I then went with him towards John Reeve's place. On Friday morning we camped a mile and a half from Forbes, and Gilbert went into the town; I heard Gardiner tell him to fetch six double-barrel guns, some rations, an American tomahawk, some blacking, some comforters and some caps, and also a flask of powder. Gilbert returned about one or two in the morning with three other men. On the Saturday morning Gardiner said, "Go on to the Eugowra Mountain", and we camped on Saturday night between Eugowra and Campbell's. On the Sunday, Gardiner rose early and ordered the arms to be loaded; I asked him what he was going to do, and he said "You'll see; if I'm lucky I'll stick up the escort." So we crossed the creek, and went on to the Eugowra Mountain, tying up our horses there by direction of Gardiner. We each had a gun; we went to the large rocks overlooking the road; Gardiner went down to the road, stepped the distance, returned, and said, "that will do." At about three o'clock someone said, "it would be a lark to get the escort horses to take them back"; it was then suggested that someone should go back and look to the horses we had left tied; I proposed to go back, and after Gardiner studied for a while, he said, "Very well, you go; you're frightened of your life, and you're the best to go." I said I had never done anything of the kind and did not like firing on men who had never done me any harm; I then went away, leaving seven men at the rocks, of whom Fordyce and Bow were two; Fordyce was under the influence of drink. I found the horses all right; while away I heard firing, several discharges; the men returned with some gold boxes, some rifles, and a cloak; the gold was placed on horses. I asked Gardiner if anyone was shot; he said, "No, and I'm glad of it; but if there had been it was their own fault, for I told them to stand, and they fired on me." When the men came back Gardiner said, "Get ready and make for where we camped last night"; we came on a piece of clear ground about a mile and a half near a creek, when Gardiner said, "We'll stop, open these gold boxes, and lighten the loads of the horses"; the boxes were opened with a tomahawk; we all had a hand in the opening; I saw the gold bags and the money taken out of the boxes; did not notice how many bags there were; I think there were three parcels; we left the boxes there, and we burnt some of the red comforters which we had used in the attack for disguise; we packed the gold afresh on one of the escort horses, and on Gardiner's own horse. We then went on. (Here Charters described the route at some length.) We crossed the river about twelve at night; we did not stay more than two hours; the registered letters were opened by the light of the fire; I heard Gilbert say, "Here's £6", as he put some notes into his pocket. After leaving this we went to Newell's, where Harry got some cans of oysters or sardines, two loaves of bread, and some gin; on leaving, Gardiner said, "Go as crooked as you can so as to bother the trackers." We went on by direction of Gardiner till we came within a few (eight or nine) miles of Forbes; when daylight arrived, Gardiner said, "make for the Wheogo Mountain"; we went on past Wheogo House, and reached the top of the mountain, where we camped about 2 p.m. on the Monday; this place was about sixty miles from where the robbery was done; after camping Gardiner went down to some rocks, and brought back a pair of scales, some weights, and some grog; we remained there for that evening. On Tuesday night it rained; we rigged a tent with a blanket; we weighed the gold, rigging up three sticks to support the scales; I assisted along with the others; as Gardiner weighed the gold, he put it on a newspaper on a sheepskin; he also counted the notes; I heard him say there were £3561 in notes; he weighed the gold off in lots and said, "there were about 22 lbs. weight for each man"; each man's share was put up in lots; Gardiner shared out the gold and notes; we gave the strange men their share, which they packed up and strapped on a police cloak or lining. Gardiner said to Gilbert, "You had better go down to McGuire's and tell him to send me some rations—enough for two or three days"; Gilbert was away for about two hours; he returned with some rations in a large dish, and he had a tin can with tea; after we had something to eat, the three strange men bade us "Good-bye", and went away. We remained at the camp till the Wednesday morning, Gardiner and I never leaving the mountain, but Bow and Fordyce and Gilbert went after the horses on Wednesday and brought them up. On Thursday we got ready to start; Gardiner said he wished he had another pair of saddle bags, and asked Gilbert to go and see if McGuire had some; he went away, but returned very shortly after in a fright, saying that as he came near McGuire's he saw a lot of police coming from the direction of Hall's towards McGuire's. After that we all got ready to start; after we got ready, we could hear the tramp of police horses coming up the mountain; we left the bottles and several other things; we had no time to shift them; we were then five in number—myself, Gardiner, Gilbert, Fordyce, and Bow; we travelled through some thick scrub, and Gardiner had got off his horse to take a drink of spirits and water, when I heard the police horses behind us; Gardiner was with me; I looked back, and saw what I thought was a blackfellow on a white horse; he was about 400 yards behind me; I could just see him through the scrub; I pointed him out to Gardiner; he said, "O Christ, here they are"; I then cantered away; Gardiner called to me not to go that way; Gilbert went in one direction, Fordyce in another; Gardiner was prodding his packhorse with the end of his gun to urge him along, till finding he could not get him along he left him; this was a very scrubby place, close to Weddin Mountains; Gardiner galloped after me, and said he had lost the gold, and it was a bad job; we asked to go back, as they might miss the pack horse; we turned, and looking through the scrub, saw three men on foot catching the horse. Gardiner then said, "We'll get on to Nowlan's, at Weddin Mountains." When I bade Gardiner "good-bye", he called me back, and said, "here's £50, it's all I can give you now we've lost the gold, and made such a bad job of it."

In cross-examination by Mr. Martin, Charters said: I have been in the colony about 18 years, and have lived at Burrowa, where I have a station with 300 head of cattle, half of them being my own and half my sister's. I have some land—I cannot say how much—but do not hold a license from the Crown for my station; there has been no increase in the stock on the station since it belonged to me. The rest of the cross-examination was devoted to various discrepancies in his evidence, Charters steadily denying that he took any voluntary part in the robbery or got any of the proceeds.

The examination occupied a very long time, and his evidence was listened to with the greatest possible interest by all parties in the court.

The next witness was a man named Thomas Richards, who was called chiefly to prove McGuire's connection with the other prisoners.

Two minor witnesses followed, and this closed the case for the Crown.

The defence consisted in an attempt to set up an alibi on behalf of Fordyce and O'Meally.

The third day was devoted to the delivery of addresses by counsel and the judge's charge.

Mr. Martin's address to the jury in defence of the prisoners was a very vigorous one. Upon Charters, the approver, he was very severe, ridiculing the idea that he had been pressed against his will into Gardiner's service, and denouncing him as a cowardly accomplice giving evidence in the hope of obtaining the reward. Pointing out contradictory passages in his evidence, he passed on to show that it had not been corroborated, except by another accomplice, Richardson, and to urge that it was therefore not to be believed.

These addresses were followed by one in reply by the Attorney-General, and by the Judge's summing up; and then the jury retired to consider their verdict. But there was some difficulty in the way, and the twelve "good men and true" could not agree. Hours passed away, and the anxious spectators and the more anxious prisoners were kept in suspense until next morning, when the jury, who had been locked up all night (having told the Judge at midnight that they could not arrive at a verdict), were called into court.

"Gentlemen of the jury," said the Associate, "have you agreed on your verdict?"

"No," said the foreman, "and there is no possibility of our agreeing."

His Honour then discharged the jury, and the prisoners were taken back to gaol, there to remain until the authorities were prepared to again place them on their trial. Meanwhile the witnesses were kept in Sydney, hundreds of miles away from home, while the numerous friends of the prisoners who had gone thither to hear the trial also prepared themselves for a lengthened stay.

But after the lapse of a fortnight the judicial machinery was again set in order, and the three prisoners were again indicted, Manns also being placed in the dock to stand his trial with them. Chief Justice Stephen presided at this trial, which followed much the same course as the previous one.

The jury retired at a quarter before eight o'clock on Thursday. At a quarter to ten p.m. the Chief Justice returned. Great excitement prevailed about the doors; and on the court being opened great eagerness was exhibited in securing places to hear the finale of the trial. The jury being again brought into court, the foreman said that they had agreed upon a verdict of guilty, on the first count, against Alexander Fordyce, John Bow, and Henry Manns; and of not guilty as to John McGuire.

McGuire was then removed from the dock, in custody, the governor of the gaol stating in answer to the Chief Justice that there was another charge against him.

The three prisoners who had been found guilty were then asked if they had anything to say why sentence should not be passed upon them.

Alexander Fordyce said he was not guilty of wounding at the time of the robbery.

Henry Manns said he had nothing to say, only he was not guilty of the charge.

John Bow said the jury had found a verdict of guilty against an innocent man.

His Honour then, addressing the prisoners Manns, Bow, and Fordyce, said: "It is my painful duty to pass on you sentence of death. Henry Manns, though sorry to add to your distress, I must say that it is impossible to avoid remarking that you are, by document before the Court, self-convicted of perjury. During the time of your trial the case has been most clearly proved against you. No man can doubt that you are guilty. You have almost intimated a desire to plead guilty; and that for the purpose of securing the escape of Bow and Fordyce, by asserting that they were not present at the robbery, and having two others arraigned in their place, apparently in order to cast discredit upon the testimony of the present informer (Charters) and having some kind of revenge on him. But of what value would your oath have been when it was known that you stated on oath that if time were given, you could prove by the evidence of your father and three members of your family that you were not the person present at the robbery, nor the person upon whom the gold was found. They have not come forward. They would not perjure themselves. And now as a last resource, you freely admit that you are guilty. The jury were quite entitled to believe the testimony on which you were all three convicted; and I am informed that the general belief in the country is that the testimony is true. I believe it to be true. There is this wickedness clearly proved against Manns, that he designed by perjury to declare Bow and Fordyce innocent. And as to the crime itself, you must know that no Government on earth having regard to the security and peace of the country, to the lives and property of its unoffending subjects, could extend towards it anything like what is falsely called mercy. I agree in the opinion that there is more mercy due to the community, to the helpless and unoffending, than to those who stand convicted of crime. It is too much the habit to lavish pity on criminals, in forgetfulness of the outrages and misery of which they have been the authors. Some consideration is due to the police, who expose their lives in the discharge of their duty, to the interest of the community, in the security of the produce from the gold fields, where there are some ruffians, no doubt, but also many hardworking, honest, industrious men, having wives and children dependent on them. See to what a state of things this lawlessness has reduced us! Here is a proprietor of cattle, who joined a band of ruffians to rob, to wound the innocent—to kill them, unless merciful Providence had prevented. There is a nest of ruffians about the Weddin Mountains; and there seems to be scarcely one about that place who is not willing to join robbers in their crime. I believe you to be all three guilty. The jury have found you guilty, and I think they are right. You stand convicted of crime. Can any one doubt the nature of that crime? Is it not a crime demanding repression by all means at the hands of the Government? For the commission of this crime, seven or eight men banded together. It was long meditated. You came unawares on your fellow men, and shot at them. If they had been dogs they could not have been shot at with more cold-bloodedness and cruelty. Some of them were shot down by men banded together for lawless purposes; no man could doubt that you deserve the punishment the law affixes to such an offence. It is not for me to say that the law will take its course; but I cannot conceive on what ground the judge could say that such a sentence would not take its course. If mercy is to be shown in such cases, the law ought to be altered, and then there will be an end of all society; it would then be simply the rule of force; the strongest would take from another whatever he chose. I believe the punishment to be just; men do dread death; but they cannot expect impunity. There is a common impression that an accomplice will not be believed. This day the world will see that the evidence of an accomplice, if it hangs together as a true story, will be believed by a jury of honest men who boldly do their duty. It is not merely the danger of the people, but the character of the community in the eyes of the world is at stake. The scenes that occur in this colony would be shocking to read of in any country. I believe that in cases of this kind, of deliberately planned robberies with cruelty and attempts at bloodshed, the only penalty men are likely to fear at all is death. If the Legislature does not think so, the Legislature must alter the law; but I have only to carry out the law as it is. I can feel for you as men, but if the taking of your lives should render the country more secure from such deeds of violence, the cause of humanity will be promoted by your extinction. Here was a reckless, bloody, murderous onslaught upon innocent men. While deeply feeling for you I feel that the interests of society are paramount, and must be defended. The sentence of the court is that you be, each of you, taken hence to the place from whence you came, and thence at a day appointed by the Executive Government, to the place of execution, there to be, each of you, hanged by the neck till you are dead. And may the Lord have mercy on your souls."

The prisoners were then removed, and the audience, who had maintained decent quietness amid all the crowding and excitement, speedily withdrew.

The Effort of Sympathisers to Save Mann

A word or two will not be considered out of place by way of comment upon the result of the first trial. The novelty of a Special Commission, and the strong doubts which had obtained in the public mind, produced by the fact that the verdict almost solely depended on the evidence of the approver, were sufficient to create an interest rarely felt in cases of either robbery or murder. And as many had expected, and many more wished, so it happened; the case broke down. The people of the west, when the news reached them, joined in the chorus, "We told you so", and the fault was laid at the door of the Government, for having fixed the trial of the men in Sydney, where, according to general impression, there was a widespread feeling of sympathy for the accused. They did not go so far, however, as to directly accuse the jury of being sympathisers with crime. Their condemnation went out rather towards the spectators, who appear from the reports in the papers to have manifested great joy at the result, and gave expression to their joy in various ways; yet even for them an excuse was found.

One writer put the case thus: "The excitement of the crowds congregated at the trials arose out of a common dislike to the evidence of an approver. The popular mind detests this kind of testimony, not merely because it is seldom to be relied on, nor indeed from any other reason as such, but from a sort of instinctive feeling which rushes at once to the conclusion that it is an augmentation of villainy. He is regarded as infinitely worse than those against whom he testifies. He is not only a thief, but a traitor. His accomplices are punished through his means, but it is at the expense of a deeper dip into crime. He saves himself, but to do that probably sends his own companions in guilt to death. What is called justice is supposed to reap some advantage; but even this is only apparent, for whilst the law wreaks its vengeance on the condemned, it lets loose the greatest villain of the mob to prey upon mankind, and the imagination pictures him as drinking the blood of his accomplices. But this particular approver endeavoured to screen himself under a declaration that he was coerced into the scheme. It would have been more creditable for him not to have urged this, as he entirely failed to make it so appear. He was disappointed, not from any unfairness of his associates towards himself, but from the loss of the grand booty. If he had received 22 lbs. weight of solid gold, and £3000 in notes as his share of the spoil, would he have delivered it up to the authorities and turned approver then? Of course this is not exactly what Government cares about, but it is the popular reasoning; and most men believe that it would be better for the accused to escape than the accuser to have his revenge."

|

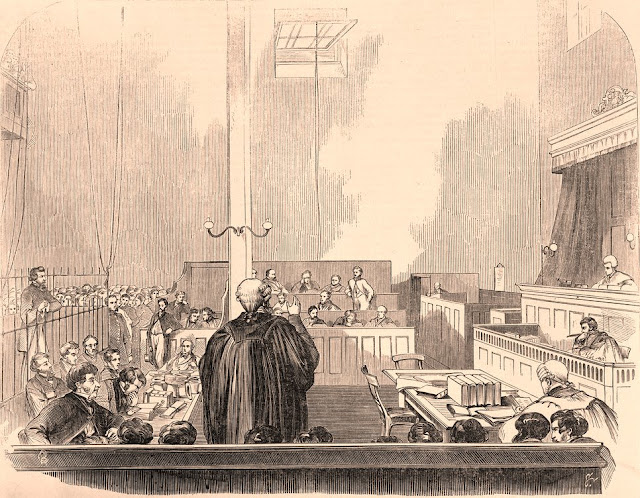

| Trial of Frank Gardiner, the bushranger, at the Supreme Court, Sydney |

There was an end to all disputing in the country, however, when it became known that three of the prisoners had been convicted and sentenced to death; but discussion was revived when the fact was made known that the Sydney people were agitating to obtain a commutation of the sentence. The result of the meeting of the Executive Council was soon known throughout the colony. The sentence of death passed upon Fordyce was commuted to imprisonment for life, but Bow and Manns were to be left to their fate. The reason for a reprieve in the one case was given. Fordyce had not fired his gun, and therefore was held less guilty of the intent to murder than his companions. This reason was a flimsy one, as the evidence showed it was through no fault of his that a bullet from his rifle did not do deadly work. Gardiner had upbraided him for not firing, and he replied "I snapped the gun, but it did not go off."

The act of the Executive in reprieving one of the condemned men made the petitioners redouble their efforts to save the remaining two. Petitions poured in upon the authorities, and the city was kept in a continual state of ferment; but the Executive Council was inexorable. They put their foot down firmly and declared they had gone far enough; there was nothing in the case of Bow and Manns to justify an extension of mercy to them. But his Excellency the Governor had a say in the matter on his own account, and having been strongly urged to exercise the Royal prerogative on his own responsibility, he yielded to the solicitations and reprieved Bow, the sentence being changed from death to imprisonment for life, the first three years in irons.

But even the Governor drew the line at Manns. Right up to the morning fixed for the execution the agitation in Mann's favour—the youngest of the condemned trio—was kept up; it was considered that his Excellency, having exercised his prerogative—the first time an Australian Governor had done such a thing in opposition to his responsible advisers—in one case, could not refrain from exercising it in the other, the two being "on all fours." One petition was presented to his Excellency with no less than 10,000 signatures attached, but the reply sent back was that the law must take its course; and on the morning of the execution he sent a message to a deputation of prominent citizens who had gone to Government House to interview him on Mann's behalf, refusing to see them and declaring that the decision of the Executive was unalterable.

The text of one of the petitions will show the scope of the whole. It ran as follows:–

Your petitioners humbly approach your Excellency and draw attention to the following reasons why the life of Manns should be spared:

1. That the prisoner is a young man who has passed his life in the interior away from all moral and religious training.

2. That hitherto he has borne a character for honesty and industry, this being the first crime with which he has been charged, and into which he may have been dragged as Charters, the approver, has sworn he was, from fear of the noted ruffian Gardiner, or by force of other circumstances.

3. That for many years previous to the 18th instant no person has suffered the extreme penalty of the law for any crime which has not resulted in death.

4. That the majesty of the law will be sufficiently upheld by penal servitude for life.

5. That your Excellency having been pleased to spare the life of John Bow, who was equally guilty, your petitioners believe the prerogative of mercy ought to be extended to Henry Manns.

Since his condemnation, the youthful criminal—he was only twenty-four years of age—had conducted himself in gaol with great propriety, and under the zealous and untiring efforts of the clergymen and Sisters of Mercy who attended him, devoted himself earnestly to preparation for the awful ordeal through which he was to pass; though it would seem he was not wholly without hope up to the previous evening that his life would be spared. This belief was intensified, no doubt, from his learning what had been done in the case of Bow, and in the strong efforts which were being made on his own behalf. But all those efforts proved unavailing, and Manns was handed over to the Under-Sheriff in due course, and by him transferred to the executioner.

His distracted mother, being anxious to have the body for interment at Campbelltown, made application for it to be handed over to her as soon as the officers of justice had finished their deadly work. Mr. (afterwards Sir) John Robertson, Secretary for Lands, who was acting for the Premier, at once complied, and the body was taken in the hearse and driven with all speed to the Haymarket; as it was feared that if the great crowd that had congregated outside the gaol walls knew what was being done they would follow and make a scene, which those acting for the unfortunate mother were anxious to avoid. Arrived at the inn where Mrs. Manns was waiting, the body was removed from the prison shell and placed in a coffin provided by the friends, and the mother and those friends having entered the mourning coach, a start was made for the railway station. But the crowd, true to its morbid instincts, had followed, and here blocked the way, and the heavy burden of the mother was made heavier by the jostling to which the mournful party were subjected. The excitement manifested had in great part been created by a rumour which had been suddenly circulated that the friends had made such haste from the gaol in order to make efforts to resuscitate the hanged man. The body was conveyed by train to Campbelltown and there buried in a grave wherein two younger members of the Manns family lay.

The unfortunate and misguided youth whose earthly career was thus cut short in a manner so horrible, was a native of Campbelltown, and many persons who knew him there as a boy spoke of him favourably as a well-conducted lad. For the last six years of his life he had been employed in looking after stock in the district lying between the Murrumbidgee and the Lachlan Rivers; and during the last twelve months had been employed on Sutherland's station, called The Gap, at no great distance from Lambing Flat. Here he made the acquaintance of Frank Gardiner; and it was commonly thought that he was one of the gang employed by Gardiner in "sticking-up" carriers and others on the road in that locality. During his imprisonment he confessed his share in the escort robbery, and more than once sought acceptance as approver with Charters.

John Bow, who was only twenty years of age, was a native of Penrith, where he was known to many persons as a schoolboy, as a remarkably well-behaved and intelligent youth. He was very respectably connected, having a half-brother and sister in very good positions in different parts of the country. He had been employed for five or six years in the Burrowa district as a stockman for different persons, but his connection for the last twelve or eighteen months with parties who were now well known to have been in constant communication with Gardiner, had no doubt led to the breaking down of whatever principles of good his earlier education may have planted in his mind, and to his initiation in the way of crime—a way that offered a broad and quickly travelled road to the unfortunate youth, and brought him to the cell over which the terrible words, "For Life" were written.

Alexander Fordyce, the third escort robber to receive sentence, was thirty-four years of age and a native of Camden. Having been attracted to the diggings, he fell in with the Wheogo mob, and then followed the downward course very rapidly, in the manner already described.

The three men named were the only members of the gang brought to trial for the escort robbery. Gilbert, Hall, and O'Meally were shot dead in their tracks after committing many other daring outrages. Gardiner was subsequently arrested, tried, and sentenced to a long term of imprisonment; but the then Attorney-General declined to put him on trial for this offence. Charters, of course, got off scot free, and located himself in the district where the robbery had taken place—but not until those who were likely to "pay him out" for turning informer had been removed.

The bulk of the stolen treasure was never recovered. What became of it is only known to the men who stole it and those to whom they handed it over: although some of the residents of the district have always held to the opinion that more than one of the "shares" so carefully divided by the leader of the gang still lie hidden in the fastnesses of the Weddin Mountains. My own opinion is that there are persons living at the time this is being written—and nearly forty summers have passed away since the robbery—who could if they chose account for the unrecovered gold and notes. More than this I dare not say.

Sources:

- THE BUSHRANGERS (1915, May 18). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 7.

- THE BUSHRANGERS (1915, May 21). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 6.

- THE BUSHRANGERS (1915, May 21). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 6.

- CAPTURE OF GARDINER, THE BUSHRANGER. (1864, June 16). Illustrated Sydney News (NSW : 1853 - 1872), p. 8.

- Trial of Frank Gardiner, the bushranger, at the Supreme Court, Sydney; Oswald Rose Campbell (1820-1887) artist; Samuel Calvert (1828-1913) engraver; Wood engraving published in The Illustrated Melbourne Post; Couresy State Library Victoria

No comments